Typically there in almost every household menu, whether it be a snack meal, lunch or dinner or simply a flash picnic meal, ranging from being savoury to sweet or deli made as well as simple and loaded with plenty of fillings, sandwiches have been undeniably had by the old and the young, at some point of time. The popularity lies in it’s ease in making it as well as having it, tapering each menu as per own individual choice.

“The idea of a sandwich as a snack goes back to Roman times. Scandinavians perfected the technique with the Danish open-faced sandwich, or smorroebrod, consisting of thinly sliced, buttered bread and many delectable toppings.” DeeDee Stovel ( author of Picnic: 125 Recipes with 29 Seasonal Menus)

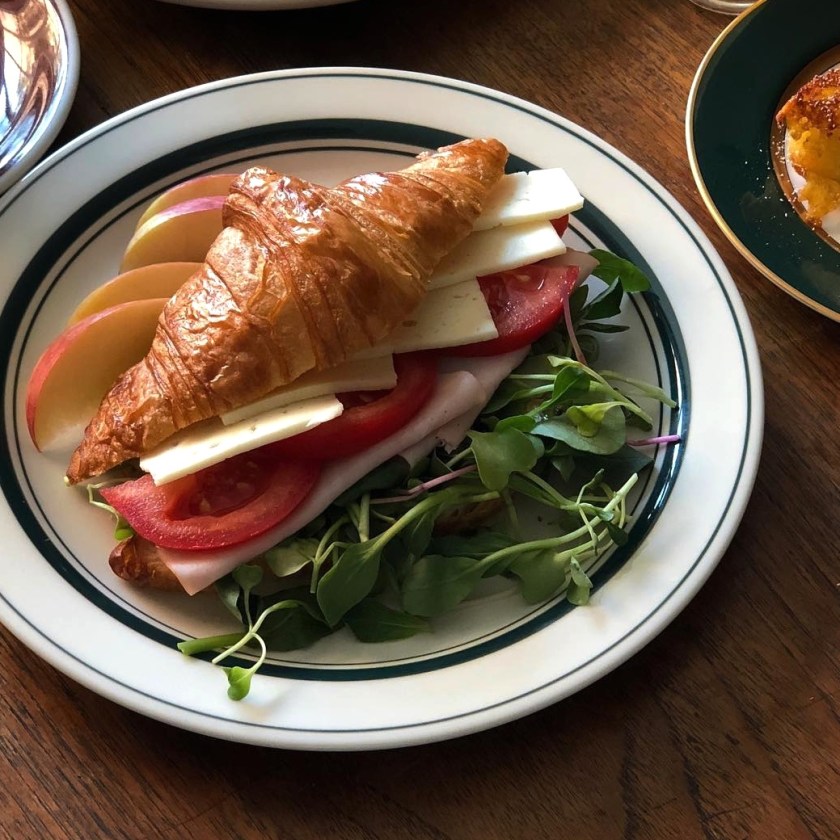

Fillings of either a savoury kind (vegetables, sliced cheese, meat and the like) or simply something sweet and buttery placed on or between slices of bread (two or more) make up the basic sandwich. Although in general, if two or more pieces of bread serve as a wrap or container holding in a set of fillings, which can be had as finger foods, constitute “the sandwich”. Though the name “sandwich” is attributed to John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich, this basic combination has been there quite earlier.

The use of bread (including flat-breads) or bread-like staple to lie over and under or simply cover up or used to scoop up, enclose or wrap up another mix of ingredients was used in such a fashion in various cultures across the continents. Throughout Western Asia and northern Africa areas, the indigenous cuisine had the use of flat-breads ( bread baked in flat rounds, contrasted tot he European loaf), whih were used to scoop or wrap small amounts of food (in a spoon like fashion) while having the meal.

As per records, Hillel the Elder (ancient Jewish sage) had wrapped meat from the Paschal lamb and bitter herbs in a soft matzah—flat, unleavened bread—during Passover (like a modern wrap). The European Middle Ages saw “trenchers” (thick slabs of coarse and usually stale bread) being used as plates. After the meal, these food-soaked trenchers were fed to dogs. Seventeenth century Netherlands had the immediate culinary precursor (with a direct connection to the English sandwich)as recorded by the naturalist John Ray that in the taverns beef hung from the rafters “which they cut into thin slices and eat with bread and butter laying the slices upon the butter”, which were served as the Dutch “belegde broodje” an open-faced sandwich.

“It’s like making a sandwich. I start with the bread and the meat. That’s the architecture. Add some cheese, lettuce and tomato. That’s character development and polishing. Then, the fun part. All the little historical details and the slang and the humor is the mayonnaise. I go back and slather that shit everywhere. The mayo is the best part. I’m a bit messy with the mayo.” Laini Giles

Moving forwards to the eighteenth century England, the popularity of the sandwich arose as the popular myth that bread and meat sustained Lord Sandwich at the gambling table (as recorded in Tour to London by Pierre-Jean Grosley). As legend goes Lord Sandwich ( being a very conversant gambler and into many portfolios for the government) didn’t take the time to have a meal during his long hours playing at the card table. Instead he would ask his servants to bring him slices of meat between two slices of bread. This habit (well known among his gambling friends) enticed them to order as “the same as Sandwich!”. Thus the terminology “sandwich” was born. Alternative account as written by N.A.M.Rodger (Sandwich’s biographer), who suggests that Sandwich’s commitments to the navy, politics and the arts meant that the first sandwich was more likely to have been consumed at his work desk. As per records the original sandwich was a piece of salt beef between two slices of toasted bread.

What was initially perceived as food that men shared while enjoying a game or drink as social nights, the sandwich slowly began appearing in polite society as a late-night meal among the aristocracy. With the rise of the industrial era and the working classes as well as the ease of making and inexpensive ingredients, the popularity of the sandwich rose in the nineteenth century. The street vendors had popularized the sandwich sales (London, 1850). Also typically serving liver and beef sandwiches, sandwich bars were set up (especially in western Holland). The sandwich was first promoted as an elaborate meal at supper, in the United States. As bread became a staple of the American diet (early 20th century), the sandwich became the same kind of popular, quick meal following the widespread trend of the Mediterranean and European cuisine.

“I love sandwiches. Let’s face it, life is better between two pieces of bread.” Jeff Mauro

By itself, sandwich has a wide range of varieties, from the simple PB&J sandwich to the more complicated fillings. Broadly mentioning the major types of sandwich include those with the two slices of bread (or halves of a baguette or roll) with other ingredients between; more complex sandwiches like club, hero, hoagie or submarine sandwich, open-faced sandwich and the pocket sandwiches. Based on the fillings as well as type of sandwich, there is the BLT, cheese sandwich, French dip, hamburger, Monte Cristo, muffuletta, pastrami on rye, peanut butter and jelly sandwich, cheese-steak, Reuben and sloppy joe to mention a few.

Few misnomers include the sandwich cookies and ice cream sandwiches, named by analogy not because of them being bread containing food are generally not considered sandwiches in the sense of a bread-containing bits. Another variant is the layer cake or sandwich cake, made of multiple stacked sheets of cake, held together by frosting or another filling type like such as jam or other preserves.

“Enjoy every sandwich.” Warren Zevon

Sandwiches, today can be filled with a variety of fillings, ingredients based on choice, availability, ingenuity and locality. From the Baloney salad sandwich to the Vietnamese Bánh mì or the Chilean Churrasco, French croque-madam, Chinese Rou jia mo, Southeast Asian Roti john, Finnish Ruisleipä and Hunagrian Zsíroskenyér to mention a few, the sandwich culture has evolved in a way. Keeping in a more creative manner fillings can range from the more bizarre like popcorn or marshmellows to Oreo cookies or the more intricate and spicy curry for a change. So when in a flurry for time, getting creative with a sandwich can o wonders for the body, mind and soul.

“I put some flour, salt, and spices in a freezer bag and then put the pieces of lamb in and then went shake-shake-shake. The lamb was nicely covered with the flour. I browned the lamb and then put it aside. Then I fried some onion with cinnamon, cloves, and cardamom, added some tomatoes and then the lamb, and cooked until the lamb was all flaky. I mixed chopped lettuce, pieces of avocado, and pomegranate seeds, along with a little bit of lemon juice. I cut the pita bread open, put the lamb curry in, and then the lettuce-avocado mixture. All done!” Amulya Malladi (author of Serving Crazy with Curry)